In cartography, technology has continually changed in order to meet the demands of new generations of mapmakers and map users.

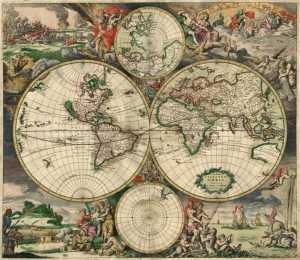

The first maps were manually constructed with brushes and parchment; therefore, varied in quality and were limited in distribution.

The advent of magnetic devices, such as the compass and much later, magnetic storage devices, allowed for the creation of far more accurate maps and the ability to store and manipulate them digitally.

Advances in mechanical devices such as the printing press, quadrant and vernier, allowed for the mass production of maps and the ability to make accurate reproductions from more accurate data. Optical technology, such as the telescope, sextant and other devices that use telescopes, allowed for accurate surveying of land and the ability of mapmakers and navigators to find their latitude by measuring angles to the North Star at night or the sun at noon.

Advances in photochemical technology, such as the lithographic and photochemical processes, have allowed for the creation of maps that have fine details, do not distort in shape and resist moisture and wear.

This also eliminated the need for engraving, which further shortened the time it takes to make and reproduce maps.

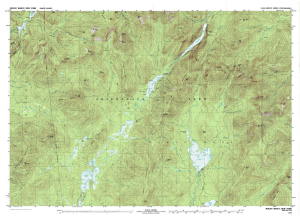

In the 20th century, Aerial photography, satellite imagery, and remote sensing provided efficient, precise methods for mapping physical features, such as coastlines, roads, buildings, watersheds, and topography.

Advancements in electronic technology ushered in another revolution in cartography.

These days most commercial-quality maps are made using software that falls into one of three main types: CAD, GIS and specialized illustration software. Spatial information can be stored in a database, from which it can be extracted on demand. These tools lead to increasingly dynamic, interactive maps that can be manipulated digitally. With the field rugged computers, GPS and laser rangefinders, it is possible to perform mapping directly in the terrain.

Ready availability of computers and peripherals such as monitors, plotters, printers, scanners (remote and document) and analytic stereo plotters, along with computer programs for visualization, image processing, spatial analysis, and database management, democratized and greatly expanded the making of maps.

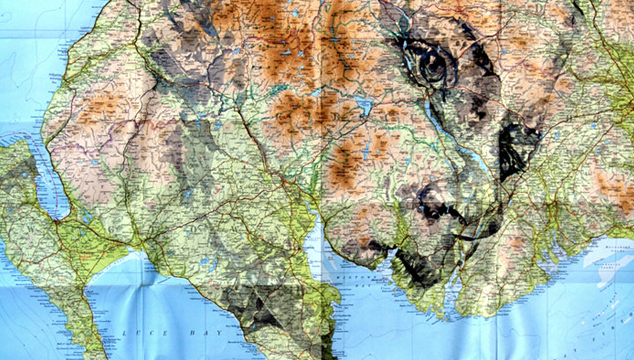

Thematic cartography involves maps of specific geographic themes, oriented toward specific audiences. A couple of examples might be a dot map showing corn production in Indiana or a shaded area map of Ohio counties, divided into numerical choropleth classes.

As the volume of geographic data has exploded over the last century, thematic cartography has become increasingly useful and necessary to interpret spatial, cultural and social data.

Thematic Cartography: A Practical Example

The ability to superimpose spatially located variables onto existing maps created new uses for maps and new industries to explore and exploit these potentials.

Mapmaking will always be an art. And the human quality of map interpretation will remain an art as well.